The Global Language Of Jazz

There’s something quietly miraculous about how jazz has travelled.

Born from the fire and fracture of the African American experience, it has crossed oceans, borders, and time zones without ever needing a passport. You don’t need to speak the same language to feel it. Jazz doesn’t ask for that kind of translation. It asks you to listen. And listening — real listening — is universal.

At its root, jazz is a conversation. Not a monologue, not a sermon. It’s call-and-response. Tension and release. A series of improvisations built on trust and risk. That’s what makes it so easy to take with you — and so hard to replicate without heart. As it left the clubs of New Orleans and crossed into Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America, jazz didn’t stay the same, nor did it lose itself. It met people where they were and let them speak back. The result is a genre that lives a thousand lives at once.

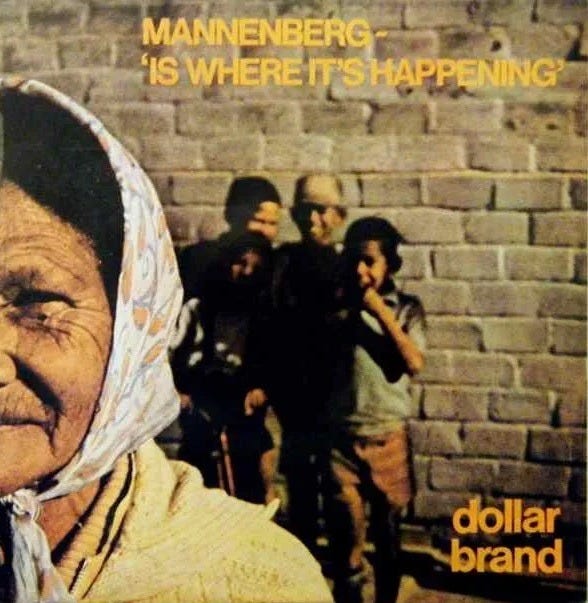

In South Africa, jazz became a weapon and a refuge. Musicians like Abdullah Ibrahim (then Dollar Brand), Bheki Mseleku, and the Blue Notes carried the weight of exile and resistance in their horns and keys. They took the raw edges of American bebop and cool jazz and infused them with the township spirit, the pulse of marabi, the voice of longing.

South African jazz carries a kind of melancholic joy — it knows about survival, about holding memory in rhythm. And when you hear a piano echoing in Ibrahim’s “Mannenberg” or the vocal chants of the Brotherhood, you’re not just hearing jazz — you’re hearing place, history, a people remembering themselves.

Move north and you’ll find the crosscurrents of Ethio-jazz. Mulatu Astatke, studying vibraphone and composition in London and New York, returned home to Ethiopia in the ’60s and created something that didn’t exist before — a fusion of modal jazz with pentatonic scales, traditional instruments, and hypnotic, circular phrasing. His music, once buried by time and regime, has since been unearthed and revered by crate diggers, beat-makers, and spiritual seekers alike. Astatke’s compositions speak of a global soul: diasporic yet rooted, meditative yet funky.

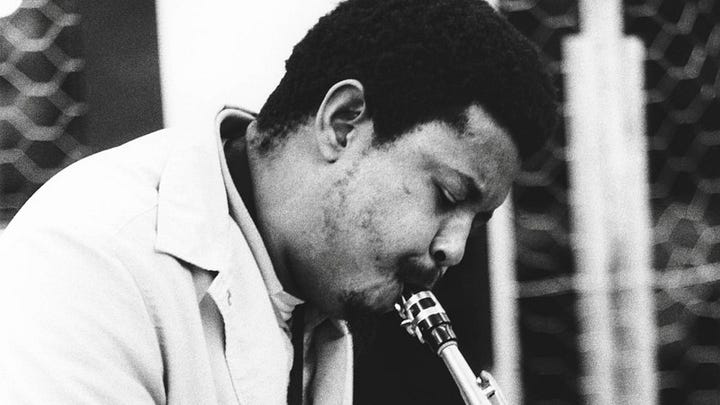

Across the ocean in Japan, the post-war era gave birth to a unique relationship with jazz. For many Japanese musicians and listeners, jazz was a symbol of freedom — both sonic and social. Artists like Sadao Watanabe, Hideo Shiraki, and Ryo Fukui didn’t merely imitate American forms; they internalised them, then filtered them through a sensibility marked by delicacy, discipline, and melancholy. The Japanese jazz scene became one of the most devoted in the world, spawning its own rich underground of smoky basement clubs, high-fidelity record bars, and fiercely loyal audiences. Even now, the devotion to analog sound and vinyl in Japanese jazz circles speaks to a reverence for the form that borders on spiritual.

In Brazil, jazz found samba. And when the two met, something soft and quietly radical emerged. Bossa nova — that subtle revolution led by João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Elis Regina — showed the world that jazz didn’t need to shout. It could whisper, seduce, and still move you. Even today, when someone drops the needle on “Chega de Saudade,” it feels like the start of a conversation you didn’t know you needed.

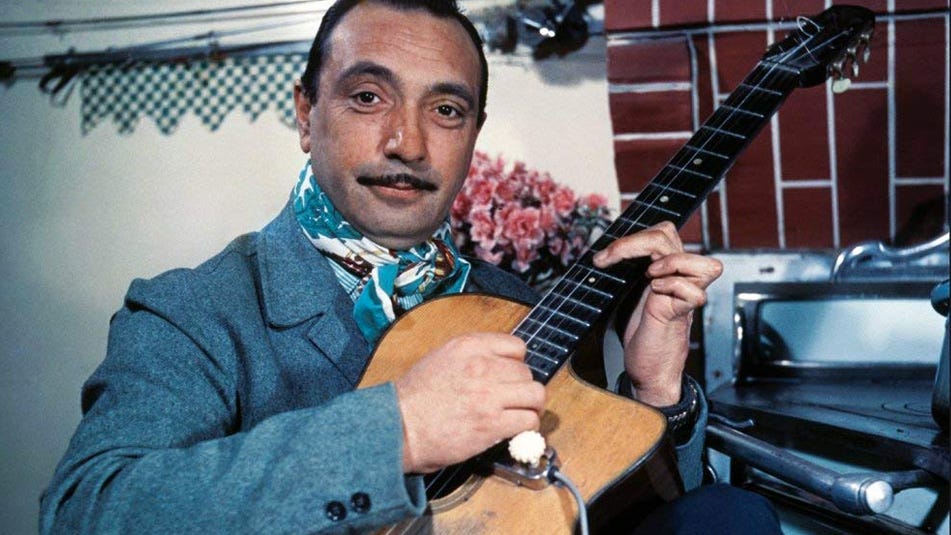

Then there’s Europe. In France, jazz found an early home in the cafés and cellars of Paris, with artists like Django Reinhardt bending swing into something singular with his Hot Club of France. Reinhardt’s Romani roots, his two-finger technique, his phrasing — all of it points to the fact that jazz was always built by outsiders, by people who didn’t quite fit but still found ways to speak.

In later decades, European labels like ECM would stretch jazz into new, ambient territories — moody, minimalist soundscapes where space was as important as sound. Jan Garbarek, Eberhard Weber, Tomasz Stańko — these weren’t household names in the U.S., but they were shaping the future of jazz in their own tonal languages.

Jazz’s journey hasn’t always been clean or easy. Sometimes it was carried by colonialism, tourism, or war. Other times it arrived through records smuggled under the table, or radio waves late at night. But no matter how it arrived, it was met with curiosity, hunger, and the urge to respond. That’s the real power of jazz — its ability to adapt without losing integrity. It doesn’t need to dominate the room to be heard. It just needs a willing participant.

In today’s hyper-connected world, you can find jazz thriving in unexpected places: Palestinian oud players improvising over modal progressions; Turkish ensembles folding in Sufi mysticism; young Ghanaian musicians sampling Coltrane and weaving him into Afrobeats. Jazz is no longer an American export — it’s a planetary conversation.

And maybe that’s why jazz still matters. Because in a time of noise and constant broadcasting, it asks something different of us. It asks us to listen. Not just to melody, but to memory. To pain, joy, silence, risk. Jazz is how we tell each other the truth, not in straight lines, but in spirals. It’s not always easy. But it’s always real.

We’re not celebrating a genre. We’re celebrating a way of being. A way of listening to the world and answering back in your own voice.

Because jazz, wherever it lands, speaks you fluently.

In Music We Trust,

Voom Voom Records